How are indigenous communities intertwined with regenerative agriculture? For native peoples, regeneration is also about reviving their culture and being resilient regardless of the new challenges. Indigenous leaders from six ethnicities shared their perspectives in a poignant debate.

Author: Ivi Pauli

Leia em português

The historic drought in the Amazon strongly illustrates that the climate crisis spares no biome. After all, we are interconnected, and this is not a choice but an undeniable fact – the action or neglect of one will affect all. Indigenous voices often warn us against idealizing their territories as an oasis for humanity when they face threatening challenges without adequate support. It becomes urgent to move beyond romanticizing this issue and actively engage in protecting what remains of their invaluable ancestral wisdom.

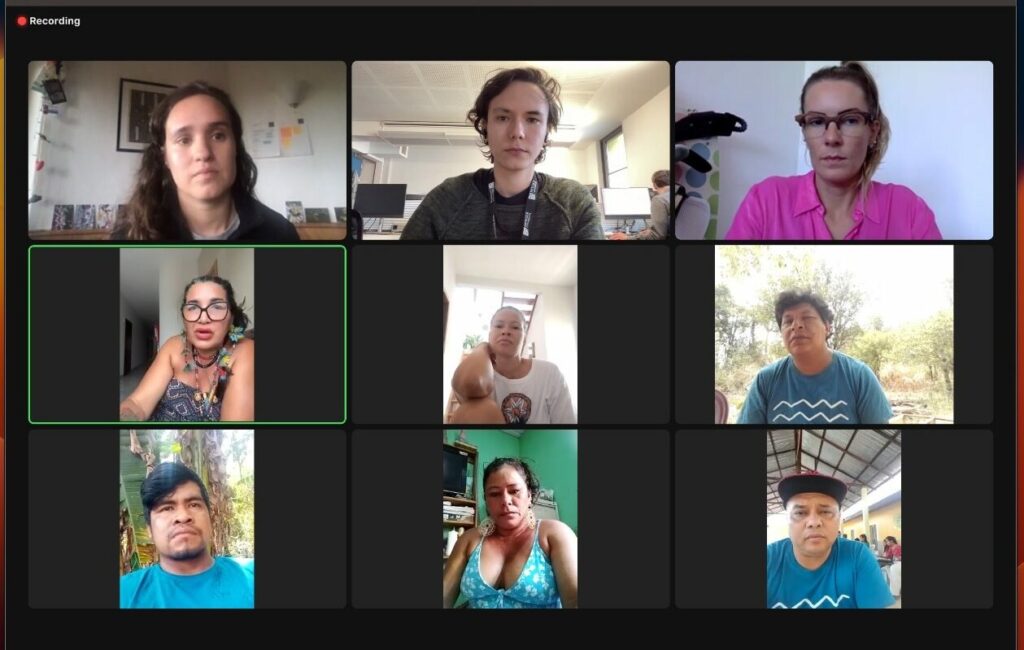

To inspire conscious action, on October 31st, Meli Bees Network and Regen10 brought to life a listening circle with indigenous leaders from six ethnicities — Apurinã, Guajajara, Kambeba, Kokama, Kopenoty, and Tupinambá — representing four Brazilian biomes — Amazon, Cerrado, Pantanal, and Atlantic Forest. Their profound insight on the current reality of their communities and a path towards a brighter future is unveiled in the following lines.

Roots of struggle: finding answers in the past

The challenges confronting indigenous communities today have deep historical roots, stemming from a violent colonization process that has left an enduring impact in the form of a persistent colonial mindset. In the past, life for these communities was characterized by abundance, in harmony with nature’s biodiversity. However, the present is marked by a pervasive sense of scarcity and disempowerment, entwined with a profound feeling of shame linked to their origins and traditional ways of living.

They taught us to cut down trees and replace them with monoculture.

Aruak Kopenoty

In a poignant discussion, Aruak shared the disheartening legacy of indigenous assistance programs, recounting how they were taught to cut down trees and replace them with foreign crops — an exemplification of the colonial use of technical assistance, which has cast a lasting shadow on the community’s ecosystem. This narrative emphasizes the enduring consequences of historical interventions and underscores the urgent need to chart a more sustainable and culturally sensitive course of action.

This is not an isolated instance. In the Agroforestry workshop conducted in the Arariboia territory, numerous participants expressed astonishment when we suggested the utilization of local seeds. This marked a deviation from traditional cooperation programs that typically introduced external monoculture seeds. In our experience, the approach of tapping into the existing abundance within indigenous communities as a foundation for collaboration has proven to be the most effective method for fostering long lasting partnerships.

Indigenous realities amidst present challenges

Indigenous communities, deeply interconnected with their unique cultural and environmental contexts, grapple with the far-reaching consequences of the climate crisis. Escalating water shortages pose a most pressing challenge, threatening both livelihoods and traditional practices in all communities of all the biomes represented in our meeting. In response to climate change’s adverse effects on their crops, these communities actively seek native edible plant species capable of withstanding extreme weather conditions — cassava being the most resilient option across all four biomes.

The loss of seeds is not only endangering biodiversity but also intricately impacting the cultural heritage of indigenous communities, disrupting the vital connection between traditional practices and the preservation of diverse plant species. In addition, as firmly pointed out by the indigenous leaders, is the effect of climate change on the predictability of natural cycles, on which ancestral wisdom is rooted, jeopardizing their ability to efficiently identify the best moments for seeding and harvesting.

It is very frustrating to plant and not be able to harvest, over and over again.

Olinda Tupinambá

External impacts further compound the challenges faced by indigenous communities. Criminal wildfires threaten ecosystems and aggravate the situation by disrupting microclimates and water cycles. Mercury from mining activities contaminates water sources, kills fish and makes people sick. Pervasive cultural interference erodes the foundations of indigenous identity. Cumulative tolls from deforestation, livestock, agribusiness, and pesticides wear down indigenous lands, challenging traditional practices.

Dependence on food aid, which is mostly industrialized and ultra-processed, disrupts self-sustaining practices that have defined indigenous communities for generations, challenging their autonomy in nurturing themselves and preserving traditional crops. The fundamental perception of what food is has been redefined as the traditional indigenous diet, rich in “non-conventional” native species, has become unfamiliar to the younger generations, who no longer recognize these vital elements as sources of nourishment. Intense advertising and availability of processed food shifted habits towards an unhealthy diet, contributing to the rise of metabolic syndromes, including diabetes and cancer.

Beyond these external challenges lies the often unnoticed emotional struggle within indigenous communities. Our conversation revealed that the loss of traditional practices and values creates a profound sense of longing, while mental burden stems from survival demands in a rapidly changing world. Emotional distress, manifesting in lacking hope and self-esteem, high rates of alcoholism, depression, and suicide weaves a complex tapestry that echoes through community lives.

Discouraged by all these challenges and motivated by aspirations for a better future, many indigenous youths are leaving their ancestral lands and migrating to urban centers in search of improved opportunities, navigating a delicate balance between preserving cultural roots and embracing the possibilities of an urban life.

Restoring hope by building an actionable path for a brighter future

When asked for a collective vision of an ideal indigenous food system, the leaders emphasized a delicate balance between nature, tradition, and community. Rooted in reviving ancestral practices while incorporating state of the art regenerative techniques, it embraces practices that nurture the soil and sustain a biodiverse ecosystem. The emphasis is on diversified food production in compact agroforestry systems using local plants and seeds. Respect for local realities prevails, acknowledging the unique demands of each community and tailoring agricultural practices to the strengths and characteristics of each territory.

Each indigenous community is very unique. Therefore, before building an action plan, we need to research the deep interplay of culture, geography and biome. Only by acknowledging context will we produce positive and lasting outcomes.

Kowawa Apurinã

Cultural and ancestral wisdom preservation takes center stage, with a commitment to safeguarding traditional seed varieties and prioritizing traditional nutrient dense foods, while empowering women in agricultural pursuits. Beyond food, they recognize the pivotal role of indigenous medicine in keeping the communities healthy and thriving in remote locations.

My grandmother is on the corner of her 100th birthday and she only relied on indigenous herbs for health her entire life.

Marciane Kokama

To underscore the magnitude of the indigenous connection to the forest, Kowawa cites the findings of bio-anthropological research confirming that the Amazon is the result of indigenous communities’ management through traditional technological practices. Over thousands of years, these civilizations enriched the biodiversity of the biome in partnership with natural cycles, revealing that these forests are, indeed, anthropogenic: cultivated and managed by human action. However, this wisdom has been ignored for too long, and today, the challenges that jeopardize our existence call for its revival.

To tackle climate challenges, for instance, indigenous leaders emphasize the importance of rediscovering and promoting climate-resilient traditional crops. To build resilience, a very specialized form of technical support—with a profound understanding and care for indigenous issues—becomes a guiding force. Leaders assert that they would benefit from insights into irrigation techniques, soil analysis, post-harvest solutions for traditional food storage and processing, as well as the marketing of their surplus production.

While it’s crucial to recognize the multitude of challenges that exist, each deserving an in-depth exploration, our primary aim here was to offer a sweeping glimpse into the profound challenges these leaders are facing and how they are coping. The overarching lesson is clear: their visionary efforts are leading their communities back to cultivating a symbiotic bond between the land and its people while nurturing a collaborative spirit within the community. This fosters an environment that encourages the exchange of knowledge and sets in motion a multiplier effect destined to reverberate through generations. By acknowledging and safeguarding the intricacies of their environment, indigenous communities are charting a course toward a future where hope is rekindled, self-esteem flourishes, and cultural resilience radiates—a vision that serves as a powerful inspiration for the entire world.

Your donation can have a positive impact on the world!

Subscribe to receive our Newsletter!

Find us also at Linkedin, Facebook, Twitter or Instagram

www.meli-bees.org

❤️

very nice piece of indigenous voices brought together !