Jataí bees in Colombia were studied in a new research led by Diana Obregon and collaborators. Are you curious to know whether animal production can affect stingless bees? Let’s understand the research and its main findings.

Author: Ana Paula Cipriano

Leia em português

In the past decades, it has been clear that pesticides, used to control insects on multiple crops, are impacting pollinators’ health and survival. As a result of several studies, some pesticides that threaten bees’ survival, for example, have been restricted or banned. However, landscapes can be complex, and pesticides may not be the only pollutants that impact pollinators.

Among the huge diversity of pollinators in the tropics, stingless bees represent the most diverse group of social bees. These bees can pollinate not only natural habitats but also crops, providing an essential ecological service. As a reflection of urbanisation, the behaviour of wild pollinators such as stingless bees has been changing. For example, instead of trees, some stingless bees can now build their nests on walls and streetlight poles, structures that were not natural to them in a not-so-distant past.

These changes in behaviours are also present when bees leave their hives to collect food. When visiting flowers, bees usually have to cope with the impacts of a changing landscape, with more pasture and animal production. In this context, a study in Colombia with Jatai (Tetragonisca angustula) led by Obregon and collaborators (2024) found that these bees are also impacted by antiparasitic medicines that are applied to cattle, such as ivermectin.

Ivermectin is a common antiparasitic medication that has a low to medium level of toxicity in mammals. However, it can be highly toxic to invertebrates. In livestock farming, ivermectin is applied to cattle – but how is it associated with stingless bees?

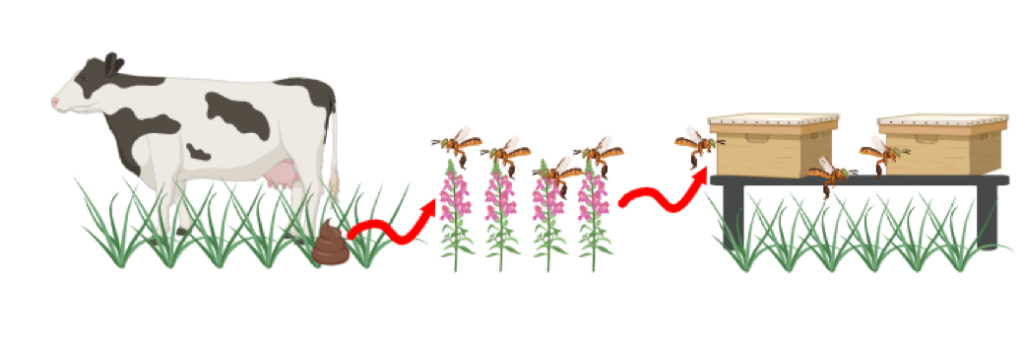

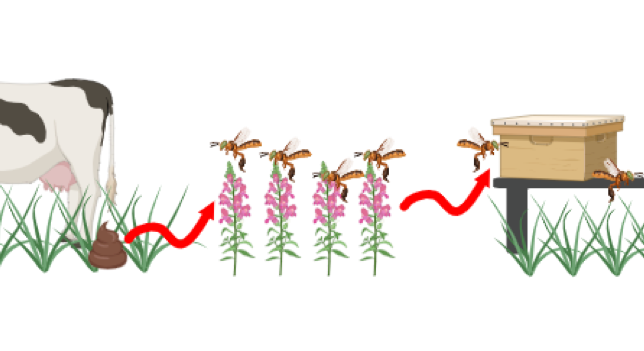

The answer may be in cattle feces and urine, once these excrements are in the soil, the Ivermectin can be absorbed by plants and, in a process called biotransformation, it becomes a different compound, the abamectin. In the study with Jatai bees, researchers found an expressive amount of abamectin in the food collected by some hives. In areas with more pasture, there was also more abamectin.

This can be a new impact of expanding pastures for cattle on native bees and pollinators, a route not explored before.

Figure: The ivermectin residues in cattle excreta may be absorbed by plants, biotransformed into abamectin, and become available resources for stingless bees. Foragers can collect the contaminated food and accumulate high amounts of this chemical in the hives. Figure adapted from Obregon et at. 2024.

With this new finding, researchers also tested the survival of bees when exposed to abamectin, aiming to understand how resistant this stingless bee can be to this chemical product. Jatai workers were fed with a sugar-water solution and abamectin. The results of this experiment revealed interesting information about these tiny bees: hives that are in areas with a higher proportion of pasture are more resistant to this pesticide. The mortality rates, therefore, were higher for bees in less cattle-dominated areas, highlighting that bees that are more exposed to this chemical are more resistant to its effects.

To protect the native bees and support pollination, it is important to understand the impacts they are facing and how to mitigate them. Instead of only focusing on traditional pesticides applied to crops, it is also crucial to investigate other sources of environmental contamination: the soil, the water and even the veterinary products applied to livestock.

Since more forests and natural resources are becoming pasture areas, the responsibility to manage the impact of anthropogenic practices on wild species should also increase. Developing high-quality research and having clear communication with stakeholders and policymakers is essential to keep stingless bees and other pollinators healthy.

Reference: Obregon, D., Guerrero, O., Sossa, D., Stashenko, E., Prada, F., Ramirez, B., … & Poveda, K. (2024). Route of exposure to veterinary products in bees: Unraveling pasture’s impact on avermectin exposure and tolerance in stingless bees. PNAS nexus, 3(3), pgae068.

Your donation can have a positive impact on the world!

Subscribe to receive our Newsletter!

Find us also at Linkedin, Facebook, Twitter or Instagram

www.meli-bees.org

❤️

One Reply to “Pasture expansion and pollinators: investigating the relationship between livestock farming and stingless bees”